Early every July, thousands of cyclists descend on the spectacular Dolomites region of northern Italy to tackle one of Europe's toughest sportives: the Maratona dles Dolomites.

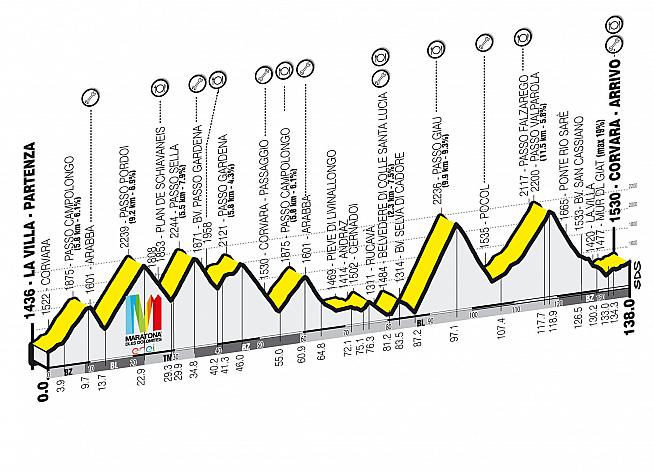

At 138km long with over 4000m of climbing, it's an uphill battle. Sportive.com reporter Jim Cotton has stomach for the fight - but after a breakfast fit to feed an entire World Tour team, has he bitten off more than he can chew?

The Maratona: Amur than a bike race

The 2017 edition of the Maratona dles Dolomites, the 31st in its history, was themed 'Amur'; love. And that symbolises the Italian outlook on the important things in life: bikes, coffee, and food. It's about passion, flair, and artistry.

In the week of the event, the host region of Alta Badia devotes itself to the Maratona; for that period, it lives, breathes and LOVES the event. There is a "Riders' week" in advance of the gran fondo in which roads are shut to traffic, cycling films are shown in public areas, and cycling is celebrated with the enthusiasm typically reserved for some perfectly al dente pasta.

The passion behind the race is like no other I've experienced. The Maratona isn't just a money-spinner, it's a celebration, nay worship, of the Dolomites. The pre-race literature was full of high-faluting gushings of the wonder of the mountains, the heritage of the area, and the beauty of the ride. The feed stations were to be stocked with locally produced cured meats, strudel from the bakers down the road, and caffè espresso was to be served to flagging riders.

As you'd expect from the love and care that the Maratona organisers put into the event, the pre-race goody bag was quite something. Along with the usual detritus of leaflets and free sunglasses cloths etc, loitered a custom Maratona jersey and gilet, both bright red, a turn away from the predominantly black colour scheme of most years - presumably in a nod to 'amur'.

Given all the attention paid by the organisers in the pre-ride litereature to ensuring that we were fully engrossed in the theme of love, making sure the riders knew exactly what delicacies were to await them at every feed station, and telling us about the Italian cycling A-listers taking to the start line, it was a charming irony that small details such as the start times and information regarding location and access to pre-race pens were relegated to the small print. It was there, just hidden.

But that's the charm of the event. It's about the beauty of the ride; the wonders of the world around us. We all know admin is dull.

Dawn in the Dolomiti

The Maratona is a fully closed road event, a rare thing for a sportive. The beauty of this is obvious; the lack of concern for coming head on to a lorry when descending at 80kph, the absence of threatening tailgaters etc. However, there was a price to be paid - a 6.30am roll out, with entry to the pens being closed at 6.15am. To avoid being stuck at the very back, an entrance as early as 5.45 arrived.

The morning proceeded thus:

4.00am - alarm

4.01am - immense anger and confusion at such atrocity

4.02am - sense of panic. Lots to be done. Lots to be eaten.

4.10am - coffee. Lots of coffee.

4.15am - huge bowl of muesli, banana, honey, and peanut butter constructed and reluctantly devoured.

4.30am - opening of hotel breakfast - second course of a few eggs and some cured ham also devoured.

4.45am - a carefully researched kit selection (following a mere 436 checks of the forecast) which had been carefully chosen and laid out the night before was donned.

4.55am - concern that, whilst food was going in ok, none of it was coming back out the other end...

5.00am - more coffee - as much in a bid to kick start my stomach as to caffeinate myself.

5.10am - procrastinate. Check weather again. Re-onsider kit. Look at other kit options. Decide to stick to the plan.

5.15am - further concern about my lack of digestive activity.

5.20am - no more time to waste - out the door, and on the bike, to the pen.

5.21am - bitter anger and resentment at my bowels and their lack of co-operation.

By around 5.40am I was in the pen.

Turns out, in what was a cold spell in the region, pre-6am in the mountains is pretty chilly. In a nod to the heritage of the sport, I'd stuffed a Gazzetta dello Sport newspaper up the front and back of my jersey to keep me warm. Back in the day it was common for riders to do this prior to a long descent to keep the wind off their chest. I had also stuck a shower cap on under my helmet in an effort to keep my head and ears in a greenhouse-like humidity. There are no tales of Marco Pantani adopting such a technique prior to a descent off the Stelvio or Mortirolo Pass, but he should have. It worked, and I looked ACE.

I had found myself in the front pen, with the VIPs, the press, and those who had achieved remarkably fast times in prior events (I'm not saying dopers, but...). The scene as Sir Wiggo, Matt and Dan from GCN.com, and Italy's finest racing snakes rubbed shoulders with portly luminaries from Pinarello, Enel, and Castelli was quite something.

I passed those interminable minutes till the flag dropped chewing down a lovingly constructed peanut butter, banana and honey sarnie, eyeing the field with a mixture of fear and amusement, and cursing my stomach situation. As we stood, already the locals were out in force bringing party to the atmosphere, with oompah bands on the side of the road, kids waving flags, and ladies handing out biscotti and sweetened shots of coffee.

Loop one: Of gongs and greensleeves

Finally, the flag drops and we're off. As I was expecting, the first 5km of gradual ascent to the base of the first climb was madness. The start of all gran fondos are super-fast, and this was super-fast on steroids. Being right at the front, where the competition amongst the finest racers of Europe is hottest, meant that the pace went from 0-60 faster than you'd be ejected from a coffee shop for a mistimed afternoon cappuccino request. On cold legs and heavy stomach I struggled and immediately lost ground.

We hit the first climb, the reasonably short Campolongo, and I was relieved. Climbing is something to be done at one's own pace, and on the steep initial ramps, I was hoping I could settle into my own competitive pace. However, within 500m of climbing, I could tell that today was not my day. The stomach was washing around with cereal, I felt bloated and sick, and the legs were heavy and slow. I had no energy and no pizzazz. I'm not used to being dropped on a climb, but it was happening. Not too much, but enough to get me pissed off.

The descent off the Campolongo was much like all of those for the day; trying to take lines that would get me around fast and safely, whilst both dodging those too nervy to descend with Nibali-like verve, but also keeping an eye out for the odd few locals who would descend at an almost unfathomably fast rate, to an extent that I did briefly have to contemplate their sanity and sense of self preservation.

The crowded peloton thinned for the second climb of the day, the Pordoi. Now that the sun had his hat on and the early mists had cleared, I got a chance to see what the Dolomites are all about. I'd been in the area for the week prior to the event, and the malevolent storms so common in the area had hidden the stunning beauty of the limestone cliffs that characterise these mountains.

The Pordoi is a beautifully switchback-laden climb through a treeless meadow; as such, the views were panoramic and spectacular, with the greens of the grasses accentuated by recent rain, and the prehistoric ruggedness of the rock formations shining brightly in the morning sun. Looking back down the climb at fellow riders swarming up the road in such a landscape, with at least half of them decked out in the bright red of the Maratona kit, conjured visions of a swarm of terrifying Jurassic red things out to do battle. To some extent they were - what is more terrifying than a carbed up MAMIL with a PB to chase?

It was on the Pordoi that I first encountered my paceman-cum-nemesis for the day.... the Guy In Blue. I noticed that myself and some Italian chap with a blue jersey, white aero helmet, and Focus Izalco kept yo-yo ing off each other, gaining or losing the odd 20 metres or so every now and then, but mostly staying together. He was to become my marker. I must beat him.

But I also didn't want to lose him. Even though no words were spoken, a familiar face (or rear wheel and ass) can be a godsend on a long day on the bike.

After an all-too-short descent from the Pordoi, we were onto the Sella, the next in the barrage of Maratona's seven punchy climbs. The thing with the Maratona is that, although the ascents are mere babies in comparison to those boasted by the Marmotte or other big beasts of the European sportive circuit, they come without respite, and some of the descents feel all too short. Thus, every climb is hit a little too hard, in the knowledge that it will only last 20-40 minutes, and the descents are a little too short to give your legs a proper chance of recovery.

The magnificent views of the Pordoi became almost eye-wateringly beautiful on the Sella. This is the pass that you see all the pictures of - the jagged rock formation at the top is so madly photogenic that it almost looks like it's been made by CGI.

I climbed in that solo trance that overcomes you on days like this, attempting to focus as much on looking at the views as staring at my stem and willing the power numbers on my Garmin to go up. The zen-like peace was rudely broken, albeit in a very charming way - a bunch of around 15 locals of varying ages had decided to find cowbells the size of oriental gongs, and were swinging them between their legs like some sort of groteque udder. The clangings were bordering on deafening. This bombardment awoke me from my reverie, and actually served to boost my spirtis; I realised I'd dropped Mr Blue - and I could just about spot him a few hairpins down the road.

The climb over the Gardena passed without incident, with the exception of seeing Mr Blue whizz past me on a long straight section of road. Much inner fury and four letter words followed.

I was still feeling grim from my unemptied belly, and the bloating feeling was becoming tiresome. With the long descent off the pass, things started moving however. Obviously yes, my bike was moving - quite fast as it turns out, hitting around 80kph - but also my guts seemed to be stirring into life. I knew that I'd be able to test the facilities and hosting of the Maratona to the utmost if I could just hang on till the facilities at the summit of the Campolongo, which we were due to tackle for the second time very shortly.

With relief for my digestive issues in sight, and drinking in the adrenaline of one of the fastest and most thrilling descents of the day, my spirits lifted.

Loop two: Gaiu, Giat, and that was that

The Maratona course is a figure of eight, and the second loop introduces you to a sense of the groundhog, as you climb the Campolongo a second time to start the second loop. Sports Tours International, who were looking after me over the event, had their own feed station at the top of the pass. They were providing their usual great service where you could leave a bag filled with food and clothes to pick up should the need arise.

I reached the feed, my one planned stop of the day, and after a swift swap around to gather some replacement pre-filled bottles, and stash ALL THE FOODS in my jersey pocket, I was away with the swiftest and securest of pushes from Sports Tours staff member Darrel; the best of soigneurs. My sense of some sort of digestive 'progress' was continuing, and after climbing the final few hundred metres of the pass to where the portable toilets were, I decided it was now or never.

I dashed into the nearest facility, having ensured there was a plentiful stock of paper and nothing that could feature in a horror film loitering in the bowl. Jersey off, bibs down, I sat. Nothing came. I sat a little longer. Still nothing.

As I sat in semi-desperation, the gentle melody of Greensleeves came drifting into the toilet - the brass band at the top of the pass had just resumed from their break and took up the tunes. It was quite relaxing.

I sat there for a few more minutes and entered a peaceful daze. The break from the physical and mental punishment of the first few hours of the race was welcomed, and I almost forgot where I was. After a few minutes of zen-like calm, I awoke from my daze and remembered them passes weren't going to climb themselves... I bibbed up and reluctantly went back to work, as bloated and grim-feeling as before.

After another sinuous descent from the Campolongo, the only flat part of the parcours awaited. Having worked hard to get into a bunch with the intent of sitting in and resting up, I found myself in what appeared to be a bit of a go-slow death march. A group of about twenty of us settled into a pace that woudn't be wisely sustained solo, but was far from progressive.

In the back of everyone's mind as we proceeded along the flatlands was the Giau. Or, as a cycling friend of mine calls it fondly, 'the fucking Giau'. It may only be 10.1km long, making it around half the length of French monsters such as the Tourmalet or Galibier, but it's just so HARD. With an average gradient of 9.1%, the opening 1km or so are easily 12% or more, and it seldom relents to less than about 9%.

There's no escape from it, no chances for a little freewheel or backpedal. What's more, the locals 'helpfully' signpost you that there are 29 switchbacks en route. Unlike many French and Alpine climbs, the Dolomites do not always have road markers informing you of the kilometers you've progressed towards a summit. Instead, on the Giau, each bend is numbered. The next 50 minutes or so were spent in a state of an unnaturally grinding cadence, trying to ignore the increasingly slowly descending numbers on the hairpin markers. I distracted myself briefly by taking off my long finger gloves as I pedalled - the sun was beaming strong, and my early morning wardrobe was getting excessive. That took my mind off things for all of 30 seconds of those 10km. Small victories.

There was some consolation from the crushing slow-motion grind of the Giau however. On entering a long tunnel about 2/3 of the way up the pass, I spied Mr Blue again. I'd lost track of him whilst in my Greensleeves reverie on the Campolongo, but there he was - back in my sights.

I thought I was struggling on the steep slopes of the pass, but Mr Blue was reeling. I could feel myself slowly pulling him back - the tractor beam was engaged and the prey was in sight. Sure, it was like a petrol tanker overtaking a cruise liner in its slow-motion glory, but I passed him and he kept going backwards. I felt like Pantani, flying to the summit of the mythical col, eating up the gradient and spitting out my opponent. It was only the dribbles of gel down my face and slight creak from my left cleat that marked me out as a gangly English imposter, I'm sure of it.

A rapid descent down a very roughly surfaced road off the Gaiu followed, and there was a sense of the field having scented the finishing line. The pace on the drop down to the Valparola Pass - the final climb of the day- tangibly increased as riders attacked the corners in the breakneck adrenaline surge that only doing well in a meaningless bike ride can summon.

The Valparola Pass was somewhat uneventful. Although long, it's pretty shallow and kind to legs that have been ground to the equivalent of stumps by the Giau. As we hit the final kilometre of the climb, we rejoined the middle group, and there were some weary souls grinding along in various states of disrepair. I probably looked just the same, but the hollow stares, heavy cadence and laboured movements of our new companions reminded me of just how tragic us wannabe racers can be.

On which note, back to the wannabe racing - the descent off the Valparola is fast and technical, and a great way to lead into the final kilometres of the ride. I was able to put my not-quite-Nibali descending skills to the test, dropping lots of the less confident in the pack. As much fun as the descent was, one thing loomed large in the back of my mind - the sting in the tail on the Maratona, and something oft forgotten about by riders as they focus on the high mountains: the Mür dl giat.

Mür dl giat translates as 'wall of the cat', and true to its name it's a 1km vicious kick in the knackers that would be more suited to the steep ridges of Kent or the Chilterns than the meandering slopes of the Dolomites. For about 600m, the climb ramps to between 15-22%, which, on fresh legs and coffee-feulled head, is quite fun. With 130km and 4000m of ascent in the legs, it's quite hard.

The atmosphere was great however, with the organisers setting up a 'fan zone' on the roadside, making it like a spectacle from the most Belgian of bergs, with pissed up locals shouting every single competitor on in a frenzy of prosecco, pizza and Peroni (other stereotypes are available).

In anticipation of the Muur-based horrors I'd saved back one last gel, and guzzled it halfway down the Valparola descent. It kicked in just at the right time, and I was able to take the Muur with some semblance of power and dignity, rather than dribbling my way up with a tear in my eye.

Over the Muur, up the final 2km drag to Corvara, round a few bends, and a 100m sprint for the line. And we were done.

As always, the next 10 minutes were a haze. A nice volunteer lady put a medal around my neck, someone thrust a bottle of sugary drink into my hand, and I staggered to the foodhall. The organisers put on a remarkable job of catering for us, serving every competitor pasta, meat, drinks, and strudel. I piled them into my face without really thinking about it, still in a bit of a daze.

Reflective musings on the Maratona

On a dodgy stomach, it had been a hard day, and one that I think I could have done better on. However, my finishing time of 6 hours, 5 minutes and 29 seconds was respectable - and I guess I can't grumble at placing 436th of the 4,500 male riders that took part in the long route. Most importantly, I think I beat Mr Blue, and I got to listen to a nice rendition of Greensleeves for a few minutes. That will do me.

In all, the Maratona is an incredible event. It's hard - damn hard - but not as spirit crushing and leg-breaking as the legendary Marmotte Alps, which is held on the same weekend. The way in which the community so gets behind the Maratona really makes it special - you feel welcomed into something bigger than a bike race, to a greater passion and, yes, love.

Even on a bad day, the environment is something else. They may not be quite as epically huge as the Alps, nor as quiet, green and luscious as the Pyrenees (my favourite mountains); however, the Dolomites offer something totally different, and something that you'll never forget. The spectacle of these unique mountains is mind-blowing.

And, if you ride the Maratona and the legs feel bad or the views are covered in mist, just hang out at the feed stations and eat all the local produce.

I didn't have so much as a mouthful along the way, in my MAMILian instincts to 'race'... maybe I need to go back next year and give them a sample. It's a tough life... but you have to love it.

The Maratona dles Dolomites returns in July 2018. For more information and to register, visit www.maratona.it.

0 Comments